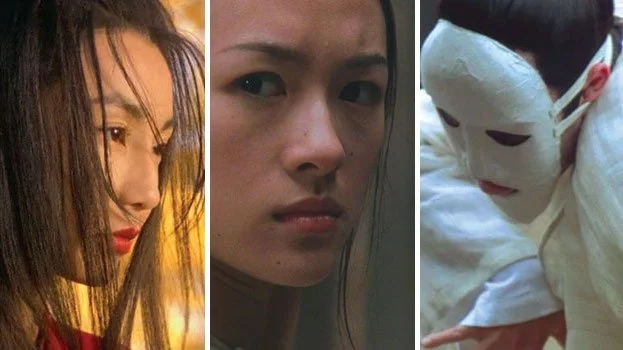

On September 12, in the Damrosch Park at Lincoln Center, celebrity composer Tan Dun led the Metropolis Ensemble in an audacious multimedia mesh of Eastern and Western sounds, forms, and philosophies as a part of the Lincoln Center Out of Doors series. On this summer evening concert, Tan Dun created a one-of-a-kind, sensory-enveloping experience for an overflowing audience with his Martial Arts Trilogy, which featured three concerto movements that were respectively based on material from the composer’s scores for the films Hero; Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon;and The Banquet.

[caption id=“attachment_710” align=“alignright” width=“300” caption=“Ryu Goto performs Tan Dun’s Hero Concerto.”][/caption]

Behind the ensemble, a large screen projected scenes of vibrant, stunning cinematography from the martial arts films. Tan Dun is well known for incorporating multimedia elements into performance, like with his 2008 YouTube Symphony, as well as for synthesizing elements from his Hunan background with his classical conservatory studies and experimental avant-garde influences. Metropolis Artistic Director Andrew Cyr described the Trilogy’s creation as an organic process; in each of the films’ scores, an instrument was featured—violin (Hero), cello (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon), and piano (The Banquet).

After the last film was produced, Tan Dun realized he could refashion the music into three concertos strung together, which eventually evolved into a multimedia project. The composer invited promising young talents to perform as soloists: violinist Ryu Goto, cellist Dane Johansen, and pianist Sun Jiyi. The piece was originally scored for a small chamber ensemble consisting of a string quintet plus winds, brass, and percussion. Later, they filled out the string section and added the Collegiate Chorale to add an epic dimension to the soundscape. In the end, the entire band shell was filled to capacity.

Recently interviewed by WQXR about the performance, Andrew, Dane, and Ryu discussed the Eastern style perspective framed within the Western concerto idiom and instrumentation. Andrew mentioned the strong Peking opera influence in the percussion music, while Ryu pointed out how the tuning system imposed on his violin referenced the complex timbres of the erhu, a traditional Chinese stringed instrument. Ryu performed on two violins (one who’s strings were tuned lower and at varying, sonorous intervals and the other violin tuned conventionally), and explained that Tan Dun hoped to represent a symbolic duality in which the two violins represented yin and yang of traditional western and eastern music. Dane mentioned the “Mongolian trill” (a series of glissandos between two points that gradually tighten in speed) that he employed on the cello to mimic technical gestures found in traditional Chinese music. He described the new experience: “It was great to witness Tan Dun encouraging an entire orchestra of ‘western’ musicians to push their boundaries and try something so distinctly ‘Eastern.’”

An interesting impact of the multimedia collaboration was the elevated emotional impact of the music. As the film scenes were taken out of order and context, and lacked any narrative momentum, the orchestra and soloists seemed to harness and project the emotions through the music that the images could not communicate without dialogue and plot. This flipped the roles of the films’ elements, as music took a dominant position as a narrator and emotional podium, while the images provided the accompanying aesthetics in the background.

The result was a powerful performance of high-flying passion and musical drama.