Program notes for the There and Back Again concert on May 24, 2007, featuring the works of Avner Dorman, Béla Bartók, Osvaldo Golijov, and Dmitri Shostakovich.

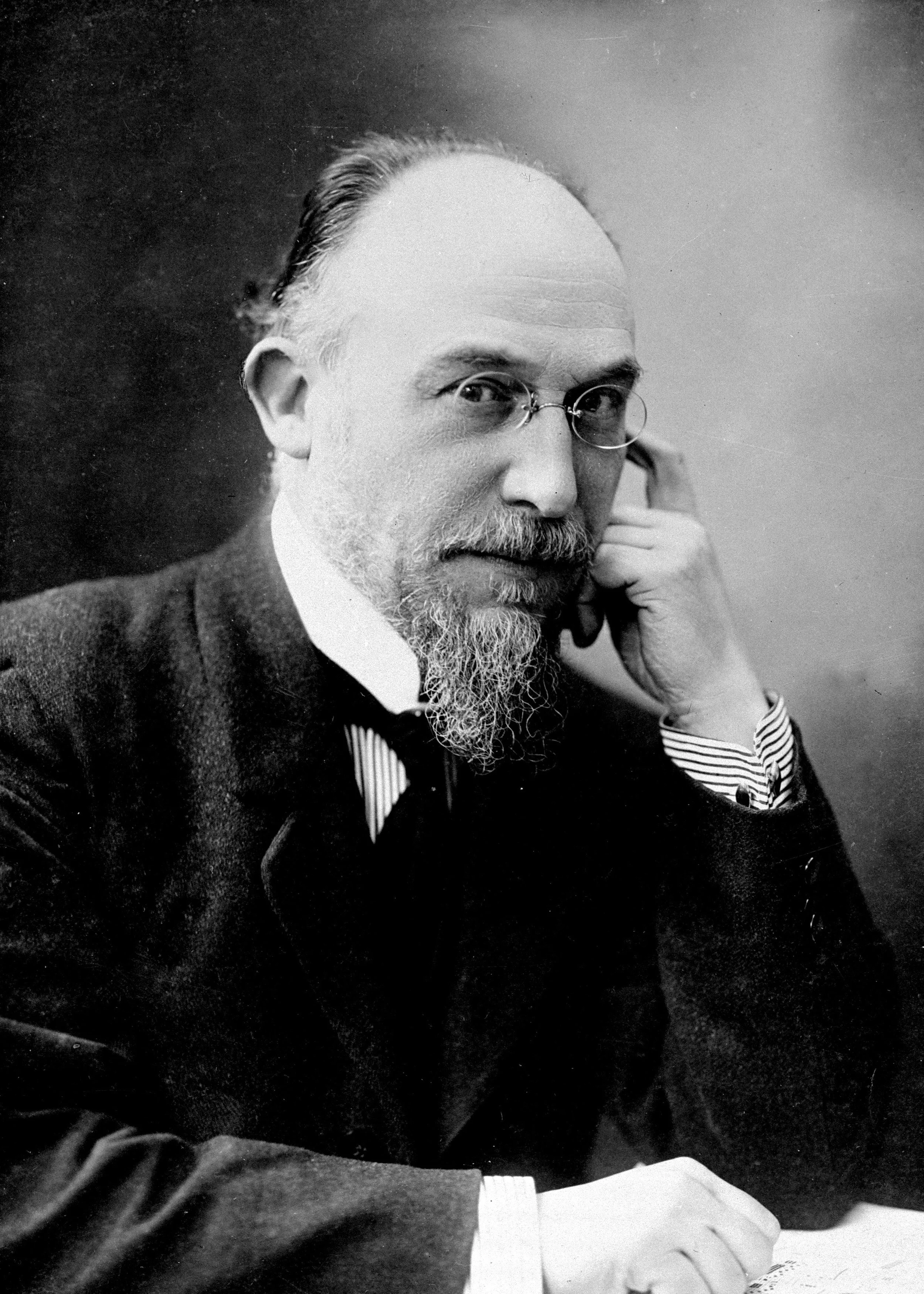

Music, self-sustaining dream of the imagination, which weaves itself out of phantom and fugitive tones, often gasps after the real. Whatever is audible in the universe has at some point, by some enterprising composer, been dissolved into music: birdsong, car horns, the chimes of clocks, railroad trains, the wordless melodies of speech, even musical representations of the sounds of musical instruments. Still, these representations, to use an eel-slippery word, can be deemed to fail. Which may be part of the reason that composers have always incorporated folk music into their works, whether secular or sacred. Folk music, a part of historical and cultural reality, is what it is (except when it isn’t, about which more later). To complain against it is fruitless: can one rebuke the sun? It is already music, therefore it nestles into the musical texture in a way that birdsong, or an attempt at birdsong, might not. And what is folk music after all but the spontaneous birdsong of the human animal, which has a thousand different voices. Folk music is authenticity itself, diametrically opposed to all art and artifice. In quest of this unquenchable authenticity Béla Bartók and his colleague Kodály tramped the fields of Hungary noting the native songs of tiny villages while, in near perfect synchronicity, Ralph Vaughn-Williams betook himself to the fens and hamlets of rural England to jot down folk ballads. When, in the fourth movement of his Eighth Quartet (transcribed for string orchestra as the Chamber Symphony we hear on tonight’s program), Shostakovich quotes a Jewish folk melody, amid a welter of reminiscences from his own and other music, it serves not only to evoke the catastrophe of the Holocaust, but also to be precisely itself, irreproachable, real. The melody is there for those who can hear it. Shostakovich can be neither praised nor blamed except for the use to which it is put: the tune is a part of living history. That said, caveat auditor. Plenty of composers have filched folk tunes and adapted them for their own use, often changing them radically. Or they have written music in a “folk style,” deriving from no extant folk music. Or the “folk” music they use may have been completely ersatz from the get-go. Exacting definitions of folk music are hard to come by. Nevertheless, all four pieces on tonight’s program find intriguingly different uses for what can fairly enough be described as folk music, whatever its provenance. In the case of Bartók’s Rumanian Dances, folk dances that he transcribed during his researches are entirely the matter of the piece. But Bartók subtly alters a chord here, varies a voice in the accompaniment there, appropriating the folk material and making its completely his own. Even the form of the piece – all six scrupulously scripted minutes (Bartók provided timings down to the second) – a series of dances in which no measure is repeated verbatim, speaks more to modernist concision à la Webern than to all night revels in the Hungarian countryside. Folk music is entirely taken up into the realms of art. As noted above, Dmitri Shostakovich quotes a Jewish melody in his Chamber Symphony. The work was written in the course of three days, after Shostakovich’s visit to Dresden in 1960, when he learned of the aftermath of the Allied firebombing of that city which claimed 140,000 lives. Icily mournful in its outer movements, often frenziedly violent in its inner, the Chamber Symphony may be, despite appearing to be a record of the destruction of war, Shostakovich’s most biographical work. Not only does it quote from many of his other works, including a very telling inclusion from Lady Macbeth of the Mtensk District of the aria “Tortured by merciless enslavement,” but his personal musical “motto” D-S-C-H (represented by the notes D, E-flat, C, B) dominates the musical material and is repeated dozens of times in all registers throughout the work. The Eighth Quartet, from which the Chamber Symphony was derived, was dedicated by Shostakovich to “the victims of fascism and war,” but can also be heard as a lament for those imprisoned by Communism and for Shostakovich himself, who had just been disbarred from the Party and feared not only for his musical career, but even for his life. Avner Dorman’s approach to folk-like material in his Mandolin Concerto is more whimsical, which is not to say that the piece itself is. The mandolin is primarily a folk instrument. Though it has been used by composers such as Vivaldi, Beethoven, Mozart, and Stravinsky, it has typically been employed in a folk-like vein. Mr. Dorman’s concerto opens with the mandolin’s defining tremolo – quickly repeated notes on the instrument’s paired strings – and broadens into slow arcs of music in which the mandolin plucks out half-melodies that suggest folk or popular origin before launching into a virtuosic Middle Eastern-inflected furiant with echoes of the tango. Of his concerto, Mr. Dorman writes: The concerto’s main conflicts are between sound and silence and between motion and stasis. One of the things that inspired me to deal with these opposites is the Mandolin’s most basic technique – the tremolo, which is the rapid repetition of notes. The tremolo embodies both motion and stasis. The rapid movement provides momentum, while the pitches stay the same. The concerto can be divided into three main sections that are played one right after another:

A slow meditative movement with occasional dynamic outbursts. The tremolo and silences accumulate energy, which is released in fast kinetic outbursts. The main motives of the piece are introduced, all of which are based on the minor and major second.

A fast dance like movement that accumulates energy leading to a culmination at its end. The tremolo is slowed down becoming a relentless repetition in the bass - like a heartbeat. The fast movement is constructed much like a Baroque Concerto Grosso. The solo and tutti alternate frequently and in many instances instruments from the orchestra join the mandolin as additional soloists.

Recapitulation of the opening movement. After the energy is depleted, all that is left for the ending is to delve deeper into the meditation of the opening movement and concentrate on a pure melody and an underlying heartbeat.

Isaac the Blind, a 12th Century kabbalist from Provence, dictated a manuscript in which he asserted that all the things in the universe are products of combinations of the Hebrew letters. Osvaldo Golijov’s Dreams and Prayers of Isaac the Blind, is a mystical and yet extraordinarily human mediation on fate as read through the history of the Jews. Golijov sees this work as mediating the worlds circumscribed by the three root languages of the Jewish people: Yiddish, Hebrew – a language both ancient and modern, sacred and secular – and Aramaic, the most ancient of all. The prayerful prelude slowly evolves like a heart that knows it is going to break. Ululations on the clarinet evoke the shofar, the ram’s horn that calls Jews to prayer, and then, more explicitly, in mutual conjunction and opposition to the string quartet, muses on liturgical melodies employed during the High Holy Day services. The second movement takes a traditional klezmer dance tune and displays it in a funhouse mirror, the clarinet wailing and gurgling in wild laughter. The clarinet takes on a cantorial role in the lush, plaintive, almost cinematic, third movement, which passes into the fluttering harmonics and reminiscences of the haunting, ultimately unresolved, postlude. The music, by turns enthralled and abject, despairing and wise, sometimes seems to come to a complete halt, only to be pushed forward by the tiniest of sonic pulses, never quite extinguished. Anyone familiar with the folk melodies used in this composition is likely to be stunned by the thrill of recognition, which is part of the point of using them, much as Ives and Copland made use of American folk song. These religious songs and popular dances of another era are a vehicle to access a time and place eternally outside the composition itself. Like the Parthenon, ever unchangingly itself, even after hundreds and hundreds of years, no matter how much it and the world and we have in fact changed, Golijov’s music takes us there, into the past, and back again.