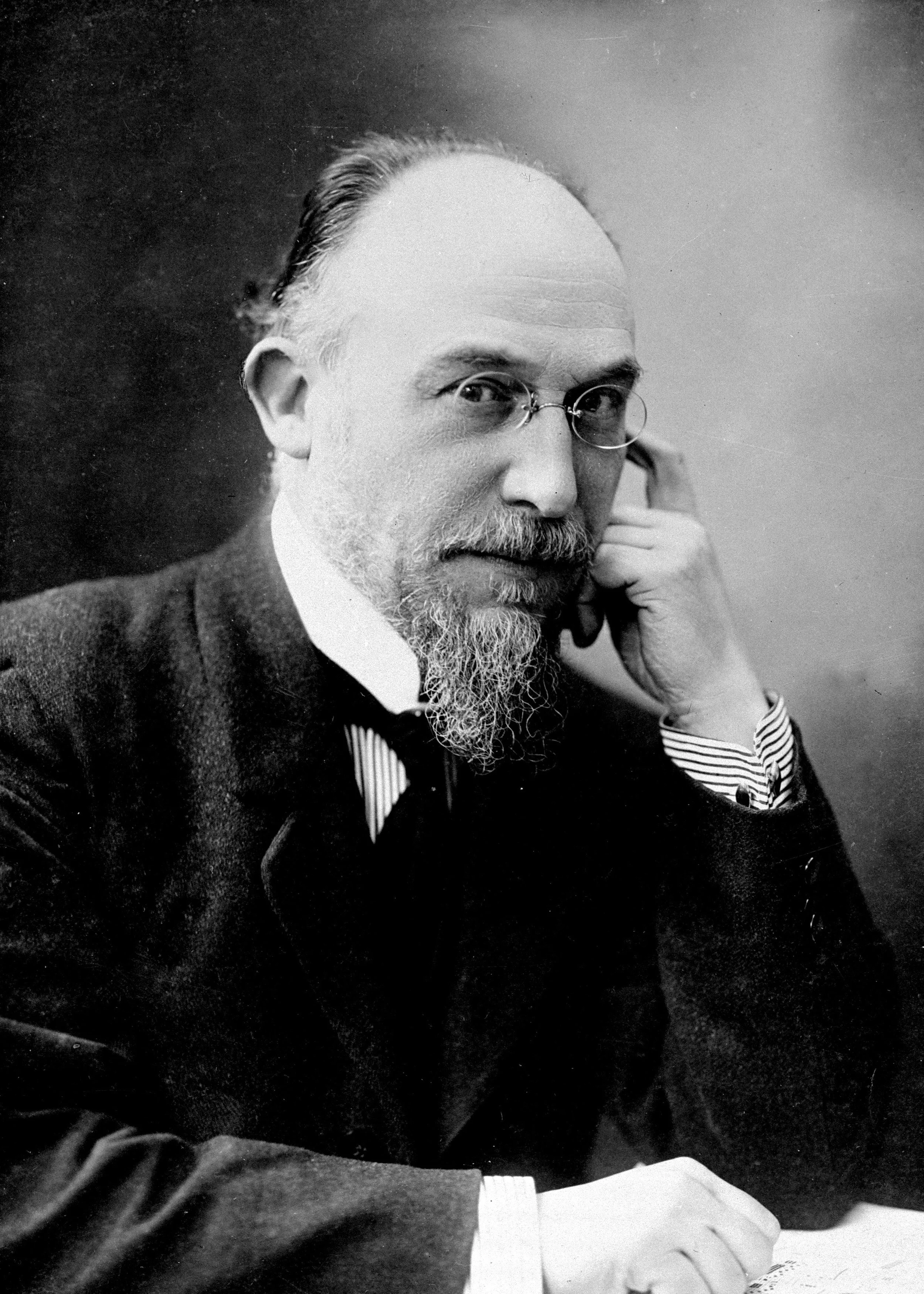

Program notes for the LOOP concert on April 10, 2008, featuring the works of Ryan Francis, Maurice Ravel, Esa-Pekka Salonen, and Erik Satie (arranged by David Bruce).

The allure of Mallarmé’s cryptic inscrutable symbolist verses inspired many composers to use them as texts – or pretexts – for composition. Nevertheless, when Mallarmé was informed by Debussy that he intended to musicalize his famous poem, L’apres-midi d’un faune, the poet replied, “I thought I had already done that.”

Debussy and Ravel had each, unbeknownst to one another, seized upon two of the three poems that comprise Ravel’s cycle for as texts for songs, a coincidence that Debussy found “a phenomenon of autosuggestion worthy of communication to the Academy of Medicine.” Ravel found his specific inspiration when Igor Stravinsky showed him the score for his Poèmes de la lyrique japonaise which employed an unusual chamber ensemble derived from one that Schoenberg used for Pierrot Lunaire. Impressed by the coloristic possibilities of such an ensemble, Ravel decided to devise his Mallarmé settings for the same combination of instruments and soprano for a prospective performance of all three works that never took place.

What Ravel achieved in these songs is less an interpretation of the texts – for, indeed, how could one interpret poems of such scrupulous, suave ambiguity? – than a supreme act of poetic transposition into music. The first song, Soupir, for example, both naively and sophisticatedly true to its title, has the arched structure of a sigh: the voice rising exquisitely to a subtle climax; and then the long sad languor of release. The string glissandi that thrum, fountain-like, behind the entire first half of the song find their etiolated echo at the end, bracketing, as if in a sad mirror, the very impossibility of the “azure.”

In Placet Futile, the vain supplication is offered to a Watteau-painted princess, as remote as a figure enameled on a china plate. But whoever this princess might be, the proud deportment of the petitioner shines clearly through angular melodic lines and intricate chromatic harmonies, maintaining inflections perfectly natural to speech. The mood is undeniably restrained, a quiet pain tightening the throat. But listen to the magical entreaty at “nommez-nous…” where the flute unfurls like a silver tongue and slowly settles to the ground like a ribbon of silver, not to seduce, for seduction requires an agency wholly absent from Mallarmé’s delicate sonnet, but to present the singer’s eternal submission on a platter of china for the perfect princess’s cool contemplation.

With Surgi de la croupe et du bond, Mallarmé pushes his text even further into the realm of music. The poem exhales a studied elusiveness that cancels form, eloquence, rhetoric. Ravel responds with music of extreme harmonic vagueness, music that even flirts, at times, with bitonality. The spare musical texture is punctured by bell-like octaves on the piano which have been heard at crucial points in the previous songs: now the knell dominates. Even the most striking effects, such as the glassy shimmer that surrounds the climax on the word “agonise,” are kept on this side of expressivity, never quite breaking through the mood of spectral silence.

Ravel, so often acclaimed for his supreme musical taste, makes these songs literally tasteful: like the taste of lime sherbet or raspberry laughs. His music does not interpret but particularizes Mallarmé’s intentional ambiguities, fixes them to a specific and eradicable flavor. It is the taste of infinite dissolution, of longing, of boredom, of chic black lacquered Nothingness.